By Dr Prosper Mutswiri

SADC Sustainable Energy Week returns to Zimbabwe at a moment when electricity has stopped being a sectoral topic and has become a regional litmus test. From February 23 – 27, 2026, Victoria Falls will host a week themed Driving Regional Economic Growth through Clean Energy and Energy Efficiency, jointly convened by the Ministry of Energy and Power Development, the SADC Secretariat, and SACREEE.

The opening will be officiated by President Mnangagwa, alongside the SADC Executive Secretary, and graced by SADC energy ministers. This is not a courtesy; it is an instruction. It signals that the energy transition is now an agenda of Heads of State, not an afterthought delegated to technocrats.

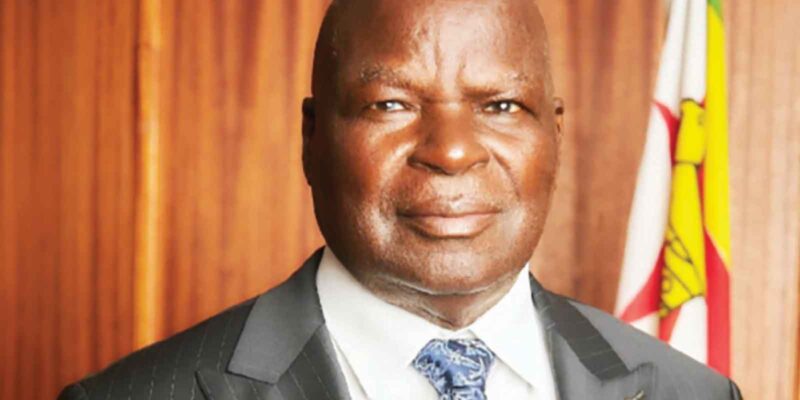

Zimbabwe Minister of Energy and Power Development Honourable July Moyo has already framed the tone in public: the meeting, he says, will focus on regional cooperation in generation, renewables, and transmission infrastructure. It is worth quoting him plainly because the sentence lands where it must land, in policy and engineering.

“We are looking at policies applicable in the Sadc region, the exchange of technologies and strengthening the Southern African Power Pool,” he told state media .

This is the right emphasis because the region cannot negotiate with physics. It simply refuses to carry the weight of industrialisation.

SADC alignment is therefore timely. The RISDP 2020 to 2030 is explicit that infrastructure development is a core pillar for regional integration and for the industrial development and market integration agenda. Energy, in this reading, is not only about supplying households. It is about creating a predictable regional platform where value chains can breathe, where capital can price risk with fewer surprises, and where cross border trade becomes a daily habit rather than an exceptional event. Victoria Falls is a fitting stage for such a conversation, because a waterfall reminds every policymaker that nature can supply abundance, but only design and governance can convert abundance into dependable power.

Zimbabwe arrives this week with a national planning logic that is already aligned, sequenced, and publicly owned. NDS 2, running from January 2026 to December 2030, anchors the development story within Vision 2030 and emphasises inclusivity as a practical organising principle. In its foreword, the document ties policy to national philosophy, and in doing so, it ties ambition to responsibility: “Nyika inovakwa nevene vayo,” it reminds the reader. This is the political economy of the Second Republic in one line: development is not outsourced, it is executed.

The Zimbabwe National Energy Compact is where this execution becomes measurable.

Minister Moyo writes that “The Compact is a bold commitment to achieving universal access to reliable, affordable, sustainable, and clean energy for all Zimbabweans by 2030.”

The Compact does not hide the baseline: as of 2022, it records that 38 per cent of the population lacked access to electricity, while over 61 per cent of households relied on traditional biomass for cooking. It then sets targets that are deliberately national in their moral language and deliberately commercial in their investment language, including universal household access by 2030 through grid and off grid solutions, expanded clean cooking access, a higher share of renewables excluding large hydro, and the mobilisation of over nine billion United States dollars in investment with a substantial private sector share. This is what seriousness looks like: numbers, deadlines, and a public accountability framework that can be monitored.

The Compact is not an isolated document. In fact, NDS 2 explicitly places universal access to reliable, affordable, sustainable and clean energy by 2030 as a national priority and ties this transition to the National Energy Compact. The same NDS 2 text is equally frank about delivery mechanisms, including a facilitated role for private sector participation in generation through independent power producers and public-private partnerships. This approach is not ideological; it is pragmatic statecraft. It recognises that the nation must lead policy, but it must also mobilise capital, technology, and implementation capacity wherever it exists.

The Compact and NDS 2 also sit inside the global covenant of the Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/70/1 defines the 2030 Agenda as a universal commitment to end poverty, reduce inequality, and protect the planet. Zimbabwe’s Compact aligns itself directly to SDG 7, and that alignment is not academic. It is a demand for energy justice, because energy poverty is a tax on every other ambition, from health to education to enterprise formation.

If there is one discipline that can make or break this agenda, it is energy efficiency. Here, the Ministerial Foreword is refreshingly direct. Minister Moyo argues that Zimbabwe must quickly migrate from inefficient energy use technologies toward green, efficient, affordable and reliable technologies as the country bids to become an upper middle-income society by 2030. The point is bigger than lighting or appliances. Efficiency is a governance ethic: it treats every unit of generated power as a scarce national asset that must be protected from waste. NDS 2 reinforces this by prioritising energy efficiency across industries and referencing ISO 50001 as a standard for efficient energy use, alongside audits and minimum performance standards. In a region where generation is constrained, this is the most rational first move.

Renewables, however, remain the central instrument for diversification and resilience. The National Renewable Energy Policy of August 2019 ties its purpose explicitly to Vision 2030 and to the national development priorities associated with private sector-led rapid growth and the national posture that Zimbabwe is open for business. That language matters because it signals continuity. Investors do not only read tariffs; they read political intent. A policy environment that declares investment mobilisation as a national priority is quietly asserting confidence in the future. The same policy also insists on building domestic capability through local manufacturing, skills development, and technology transfer, because a transition that imports everything is a transition that exports jobs.

This is where international sustainability and ESG standards become more than fashionable acronyms. In June 2023, the IFRS Foundation announced that the ISSB had issued IFRS S1 and IFRS S2, positioning them as a common language for sustainability-related disclosures in capital markets. This is an important shift for the region because capital is increasingly conditional on credible disclosure of sustainability risks and opportunities, and on the governance that turns disclosure into performance. The Zimbabwe National Energy Compact is already written in a style that understands this reality. It speaks of de-risking mechanisms, competitive procurement, regulatory certainty, and transparent monitoring systems. Those words are not decorative. They are the grammar of bankability.

From the standpoint of ESG scholarship and practice, the stakes are clear: the region must refuse greenwashing and insist on measurable outcomes. In recent peer-reviewed work on ESG shortcomings in Sub Saharan Africa, the evidence is that selective disclosure and weak assurance can produce impressive narratives without corresponding performance, and that stronger governance and independent auditing mechanisms are essential to protect public trust and investor confidence. The same research logic, when applied to energy, leads to a simple principle: megawatts announced are not megawatts delivered, and impact claimed is not impact verified.

Yet the promise is equally real when ESG is implemented with discipline. A systematic review on ESG integration in African agribusiness points to positive links with productivity, food security, rural livelihoods and long-term resilience, while also acknowledging the barriers that require tailored strategies for African contexts. Energy access and clean cooking, in this sense, are not only energy sector outcomes. They are agricultural outcomes, health outcomes, and industrial outcomes. They are the infrastructure of dignity.

The Mutapa Investment Fund sits in the middle of this national and regional story because energy investment is not merely about constructing assets; it is about governing assets. The Fund describes itself as Zimbabwe’s sovereign wealth fund, created to provide strategic leadership and oversight to portfolio companies, leverage balance sheets, apply sound corporate governance, and foster partnerships with global investors for sustainable development. Its stated purpose is to anchor long-term sustainable growth in line with Vision 2030. Crucially, the Fund’s portfolio includes an Energy and Trading cluster that lists ZESA Holdings and its subsidiaries, including PowerTel Communications, Zimbabwe Power Company, and the Zimbabwe Electricity Transmission and Distribution company.

This is why the design of the Victoria Falls programme is important. It includes National Energy Compacts progress deliberations, and the organisers state that the week coincides with member states developing or finalising National Energy Compacts under Africa Mission 300. This is where the week must become most demanding. It must ask what has been financed, what has been procured, what has been commissioned, what has been connected, and what has been measured. It must insist that the language of targets be matched with the language of procurement and construction, and that the language of investment be matched with the language of governance and disclosure.

Zimbabwe is not short of ambition, and that is precisely why it must not be short of discipline. NDS 2 speaks openly of bold and transformative interventions to drive reforms central to Vision 2030, while the Energy Compact states its targets without ambiguity and calls for partnerships that leave no one behind. A patriotic reading of these frameworks is simple. The country is being asked to build. The region is being asked to integrate. The private sector is being asked to invest. And every actor is being asked to report honestly, because the era of unverified promises is over due to the growing demand to disclose.

Victoria Falls, therefore, should not only host a conference. It should host a reckoning with reality and a recommitment to competence. The most persuasive politics in development is not found in slogans; it is found in lights that stay on, industries that produce, clinics that refrigerate medicines, schools that teach with power, and households that cook without sacrificing forests and lungs. Under visionary leadership that has kept Vision 2030 at the centre of national planning, Zimbabwe has chosen a path that is clear in its documents and increasingly visible in its delivery architecture. It is clear that the SADC Sustainable Energy Week 2026 will prove that the region can match clarity with execution, and aspiration with actual power.

Dr Prosper Mutswiri is an ESG Expert and Commercial Executive. He writes in his own capacity, and his views do not represent the company. He can be contacted at [email protected]

Comments